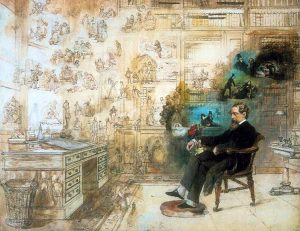

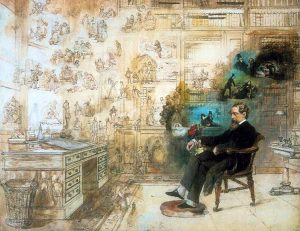

In the well-known painting Dickens’ Dream by Robert William Buss, the artist depicts the author in his study, deep in thought, and surrounded by the illustrated fumes of his own imagination, brimming with that panoply of characters for which he is so famed. Were we to repeat the somewhat sentimental exercise for our seventeenth century poet Hester Pulter, we might wonder what the vapours of her portrait would reveal. Images of those she knew or knew of in her own era would undoubtedly abound: her family, her friends, her politicians, her king. Various pagan gods would join the pageant, from classical deities like Aurora to the spirits of her local streams. Yet alongside these human or seeming-human figures, a great quantity of animals would surely find their way amongst the haze for, as it is impossible to picture Dickens without his fair young heroines and grimy orphan boys, so it would be quite remiss to illustrate Pulter’s mind without her vast poetic zoo.

In the well-known painting Dickens’ Dream by Robert William Buss, the artist depicts the author in his study, deep in thought, and surrounded by the illustrated fumes of his own imagination, brimming with that panoply of characters for which he is so famed. Were we to repeat the somewhat sentimental exercise for our seventeenth century poet Hester Pulter, we might wonder what the vapours of her portrait would reveal. Images of those she knew or knew of in her own era would undoubtedly abound: her family, her friends, her politicians, her king. Various pagan gods would join the pageant, from classical deities like Aurora to the spirits of her local streams. Yet alongside these human or seeming-human figures, a great quantity of animals would surely find their way amongst the haze for, as it is impossible to picture Dickens without his fair young heroines and grimy orphan boys, so it would be quite remiss to illustrate Pulter’s mind without her vast poetic zoo.

From lamb to eagle, lion to unicorn, hare to hydra, the works of Pulter throng with animal life. There are industrious insects like the ants who lug their “flatuous issue” up and down, wild birds like the halcyon who “calms the ruffling seas” and monsters like the whale who “plays in sports and makes mad reax in Neptune’s azure courts.” We are told of ravenous ravens, stately harts, humble tortoises –and even the likes of the basilisk, the phoenix and the chimera make an appearance.

Animals are, of course, present in the work of many of Pulter’s contemporaries but for her they take an unusually central role, particularly in the poems she calls her “emblems”. Popular seventeenth century emblem books, like that of Francis Quarles, are filled, not with animals, but with images relating to man: globes, crowns, haloes, hearts, hands, human beings and personified concepts like Love or Death. In a digression from the norm, Pulter uses animals in the majority of her emblem poems, marrying Aesop-like fables to a genre whose focus was always the spiritual dimensions of the human experience.

If we unpack the function of Pulter’s animals further we find that two distinct types (or, perhaps, breeds) of creature emerge.

The first breed is the ‘bad’ animal. In a world where Genesis decreed that man was created superior to the beasts, many early modern moralists used animals as a standard of sub-morality to which the upstanding Christian should be careful not to drop. Animals represent vices: the wrathful lion, the cunning fox, the greedy crane—in fact, one imaginative Elizabethan text depicts the various states of drunkenness in the form of different beasts.

In keeping with this convention, Pulter’s emblems occasionally utilize bad animals to criticise particular behaviour. We meet the dubiously maternal ape who shows her care for her children by “huggling that she loves until it die, the other [wrawling] at her back hangs by” and who thus becomes a warning to human parents that favouritism is not only a vice but an apeish vice and one which they should scorn to imitate. Similarly, vanity is embodied by the tiger whose “self-loved beauty makes her in a maze”, and who is subsequently caught by the hunters. Though an unflattering comparison to those accused of similar vices, this ‘bad’ breed of animal is essentially unthreatening; these creatures merely remind us that man is morally superior to the beasts and that he should, at all costs, avoid a close resemblance to these his natural inferiors.

More abundant and more challenging in Pulter’s work is that other breed of animal, the ‘good’ animal. It is surely a far more dangerous suggestion (and a digression from much early modern discourse) to imply that beastly nature might at times excel that of human beings, yet this is precisely the statement which many of her poems make. In emblem 24, for example, the conjugal bliss of the marmottanes (a large rat-like rodent) is held in scathing contrast to the unhappy love of human couples. Pulter says of human men that “most to taverns or to worse will roam, or else they’ll always tyrannize at home” adding “if such do read these lines to them I say; the rat of Pontus’ lovinger than they”.

Stern criticism indeed. And all the more stern for its implication that man, through his failings, has lost the right to call himself the moral superior even of a lowly rodent. This troubling use of ‘good’ animals to highlight human error also assumes a political purpose in Pulter’s work as, writing with Royalist sentiment during the years of civil war, she praises the natural loyalty of animals whilst men themselves have spurned their rightful king. The elephant in emblem 19, for example, humbly bows its knee to its proper sovereign, the sun, whilst a lack of such steadfastness in man “did make us bleed in our brave king. For had you valiant been, so sad a change as this we ne’er had seen.” Man has not sunk to the level of the beast, rather, the ‘good’ animals have come to surpass him in virtue, transgressively reordering God’s intended hierarchy of living things.

It is a startling feature of her work then, that Pulter not only brings animals to centre-stage in poems explicitly concerned with human nature, but that she makes challenging use of them to draw unflattering comparisons between beasts and man and constantly asks the reader to reassess their moral position in relation to the animal world. There is a huge amount of research yet to be done on this unique seventeenth century poet, but of all the aspects of Hester Pulter’s work, the menagerie of her imagination is clearly crucial to the critical and symbolic function of her poems. When drawing that fond, Dickensian image of Pulter at her desk, we would do well to remember that it is not just the human silhouette that may be found strolling through the vapours of her mind.

Pulter’s Poems, Emblems, and The Unfortunate Florinda is published by the Center for Reformation and Renaissance Studies (CRRS) as part of The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe series.

Pulter’s Poems, Emblems, and The Unfortunate Florinda is published by the Center for Reformation and Renaissance Studies (CRRS) as part of The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe series.